Hearts on Fire

22 Aug 2012 :: by sd :: Comments

James Arthur Ray :: the play … okay?

Tickets are $15,000 :: no refunds … or complaining.

Okay maybe not :: tickets are some other price that won’t tend to make random people on the interwebz exclaim … “you deserved to die!”

But getting to Scotland isn’t easy :: unless you’re Mary Poppins … or god. Fortunately I am :: god that is … not Mary Poppins.

Okay maybe not :: but I do have interesting and articulate readers all over the world … including The Scot-lands. It makes me feel quite powerful :: so don’t even come at me or I swear to the magical universe genie … I’ll have your ass theatre reviewed … so hard.

Our own @DrGeek attended the show and filed this report with my fake secretary Debbie. She spilled nacho cheese all over it and I had to request a second copy :: because it was most def worth printing … without the cheese.

I wasn’t sure what to expect.

The promotional video promised to take me in to the sweat lodge, and to hear the stories of those who’d survived … and those who hadn’t. But how could a play even hope to convey the horrors of that day?

The general mood on the blog was skeptical; there was a fear the production was in poor taste and would cause further pain to those who had already suffered too much.

But this was also a story which needed to be told…and not just told, but understood.

Because, if you didn’t understand, it was far too easy to blame the victims, to speak of “personal responsibility”, to think you might have done differently. For the play to be a success, it would have to explain why this was false.

I needn’t have worried; it’s a very powerful piece and, I believe, an excellent representation of the events. Listening to fellow attendees talk about it on the way down the stairs, I heard “terrifying” used a number of times, as well as “really unsettling”.

There’s a reason for this.

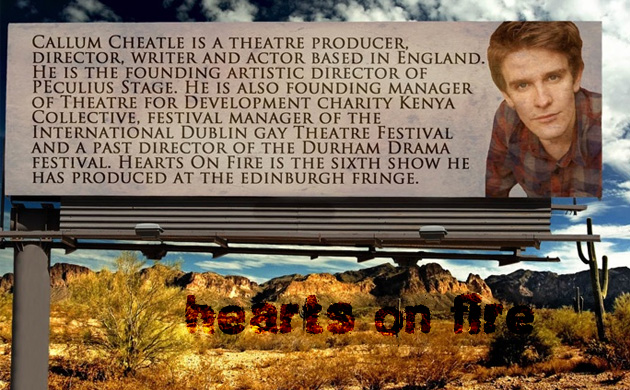

The play was born when producer Callum Cheatle read this report in The Guardian and realised the story would make for an excellent piece of immersive theatre. It also needed to reach as wide an audience as possible.

He then commissioned Adam Usden to write it; Usden then immersed himself in the world of James Arthur Ray, reading all of his books, watching his presentations and YouTube videos, in addition to all of the eye-witness accounts and Connie Joy’s book, “Tragedy in Sedona” (he describes the latter as a “fascinating and slightly disturbing account of being part of Ray’s inner circle, condemning him, while still, very obviously, in thrall to him”).

Most of the dialogue is verbatim; frequent use of direct quotations from eye witnesses and JAR’s own presentations means the dialogues rings true. Nigel Barber acts with a ferocious intensity, and the way it’s staged allows the audience to experience the full force of JAR’s personality.

It was an unusual venue, to say the least. Edinburgh’s annual Festival and Fringe is so large the city’s traditional venues hold just a fraction of the events, with all sorts of buildings pressed into service. Hearts on Fire is at C-Nova, in the India Buildings, formerly home to Edinburgh’s registry office. The top floors of the buildings have, for the duration of the Fringe, been given over for “immersive theatre” and it’s here Hearts on Fire is performed.

We were met at the door by a “Grace”, JAR’s event co-ordinator, who wished us luck in our “journey to become a Spiritual Warrior”. Stepping inside, we could see the room had been carefully set up to look like the inside of the sweat lodge, a tarpaulin and canvas dome over a sandy floor with benches around the outside for us to sit on as events unfolded in front of us.

We were welcomed again inside by “Sam”, a slightly fey male JRI employee, with any latecomers or people talking stared down. The lights went down, and when they came up “James” was in our midst.

He spoke about the events of that day, expressing sorrow and regret, and I feared this was a major mis-step. But I had little time to think as the play moved on with “James” moving seamlessly into a blistering delivery of his very own hodge-podge of mysticism, misunderstood quantum physics and the law of attraction.

The play wasn’t limited to the events of the sweat lodge; it covered the run up to the sweat lodge, as well as the lodge itself, and focused on four participants, with varying degrees of commitment to JAR.

The portrayals seemed accurate; all of them were seeking something, a couple were rather new age-y, and there was a member of the “inner circle” who seemed infatuated with “James” more than the others. There was a painter, looking to settle down; a family man, a fun-loving goofy Irishman desperate to keep growing so he didn’t give up like his father did, an enthusiastic Orthodontist smitten with James Ray, and a grandmother who was a member of his inner circle.

Although they might seem a little clichéd (a criticism some reviewers have made of the production), I’d disagree. Clearly based on the actual victims, the characters were sensitively portrayed by the actors; they were likeable, resourceful and, above all, real. “Karen”, the inner circle member, was perhaps the most reserved, but she thawed during the recreation of the “Vision Quest”, feeling the full force of James’ anger when she was caught sharing cake with “Leah”, the painter who had missed dinner after “dying” in the Samurai Game.

A number of key events were included; while some volunteered to have their hair cut, some had their hair cut without consent (hair cut but not shorn, presumably because it’s easier to cut off fake hair extensions than to have an actor grow their hair in a day) and, as I’ve mentioned above, the Samurai game was also included, with James’ bellowing “die” at a confused participant he’d tricked into talking to “God”.

“James” was truly terrifying, spouting nonsensical mash-ups of Quantum Theory with aggressive confidence, playing to the crowd with the Black-Eyed Peas “I Got A Feeling” blasting. And we were also taken backstage where, in private, he capriciously switched between charm and cruelty, changing into identical T-shirts and leering at his assistant, then berating her for letting him leer.

Later, we had to watch as he destroyed “Karen” (the “inner circle” Spiritual Warrior) for offering food to one of the actors who had been “killed” in the Samurai game, making her all the more determined to complete the “sweat lodge” to earn back his favour. I don’t know if the production team knew about the death of Colleen Conaway, but it was chillingly easy to see how being on the wrong side of JAR’s contempt could lead to psychological instability. Around the same time, his cold indifference to the orthodontist’s decision to cut her hair betrayed the contempt he felt for his customers.

The lodge itself was a smaller part of the production than I had originally anticipated, although in retrospect this was understandable. You couldn’t hope to understand why the victims behaved like they did without some context, and it also wouldn’t be possible to portray the full horror of being in that lodge.

What we saw was “James” cavalierly ordering more heat, more stones, talking about how his lodges were the hottest, that they were like hell, telling those who wanted to leave how he thought they were “better than that”, coercing family man “Daniel” to stay even though he wanted to leave, with James replying to Daniel’s plaintive explanation “I’m just thinking of my kids” with a chilling “I’m thinking about your kids”. He also screamed at one for pulling up a flap and “destroying the sanctity of the lodge” - this was the only one of the four “Warriors” who survived.

And all the while he ignored the agonised cries of his “Warriors” and the warnings that some “weren’t looking too good”, dismissing them with his infamous “the door’s closed, we’ll deal with that later” comment … then the participants stood up, the lights went up, they stood and spoke their thoughts - the final thoughts of three of the four (obviously a dramatisation, but believable)- before the lights went back down and the assistants raced in to a maniacally delirious “James” (who had indeed been sitting by the exit, although they didn’t make much of this) and then realised the others weren’t breathing before starting ineffectual CPR in a panic.

And, even here, things were beautifully observed; while event co-ordinator “Grace” started CPR, “Sam” said “But I’m not trained”; JRI’s event co-ordinator Melinda Martin had been trained in CPR but others apparently had not been. While this was happening, “James” walked off to his corner (out of the light, undoubtedly indicating his room) and stripped down to his underwear before changing his attire once more.

He then resumed his speech from the start, expressing remorse, but with huge amounts of self-pity creeping in (“I wanted to take them by the hand and see how they had changed…that was for me. Everything else was for them but that was for me!”. He then wound up to a tearful, self-pitying but apparently penitent conclusion … and I thought “what a shame - they’ve failed at the last. He’s a sociopath - he can’t be sorry”.

And then the only survivor of the four came back out, and sat in what had been his chair, dressed in a black skirt and top, giving a media interview … and it became clear he wasn’t sorry for causing their deaths. He was sorry he was in trouble, worried how the bodies “right there in front of me” could be squared with his professed belief in the law of attraction.

The survivor, using Beverly Bunn’s words, then gave a cold but clear account of the chaos and of how James Ray had done nothing, showered and changed and then just stood. “He helped … no-one”. As she was speaking, we also hear JAR’s internal monologue (“Don’t you dare! Get out of my chair. You dare sit there and criticise me?”). All this time the dead remained on the floor, like an extended version of the Samurai Game.

And then he was back holding court “what happened … happened. You think this is going to stop me?” He built up to a peak a modified version of the “you’ll think you’re going to die” schtick, and finished with “I haven’t even started my engine; turn it on … are you ready … Go!” and the lights went out … the end of the play.

Had I not known this story before seeing the play, I’d have assumed the events had been dramatised; I suspect many attending might think the same. But this isn’t the case; here many of the more outlandish details are minimised or ignored entirely (although the $250 ponchos are mentioned, it’s a throwaway line, something many audience members might think a joke … but it is of course true); in the play the cost of the weekend is $10,000 with flights and accommodation; in 2009, these were separate (and came to another $5000, with attendees unaware the “special rate” they paid for accommodation was actually higher than the usual daily rate).

Participants were also encouraged to forego sleep in order to fill out deeply personal questionnaires, which is only briefly alluded to. There’s no mention of any previous issues at JRI events, no mention of the high pressure sales tactics for even more expensive events a day or two into the course, and no mention of the participant who tried to leave with her sister, only for the “Dream Team” to try to prevent her doing so, saying her sister was “having her own experience”.

These omissions are understandable; they would’ve taken too long and, ironically, would have placed too much strain on the audiences’ credulity.

The production isn’t trying to explain why people attended; rather it focuses on an accurate portrayal of the events. Callum Cheatle felt the story had to be told as it “carried an urgent message, in a new age of dangerously plausible versions of faith.” It’s seductively easy to think we would have made different choices than the participants, but would we? Hungry and dehydrated after 36 hours spent in the desert, then into a sweat lodge with a man like James Arthur Ray, coercively encouraging us to “complete” an experience we’d paid ten large for as we became more and more heat exhausted and delirious? Or would we have trusted him and his assertions that we’d “feel as if [we’re] going to die but it’s OK”?

We know what we’d like to be true, but would we really be able to resist the coercion when we were drained, dehydrated and delirious?

>> bleep bloop

comments